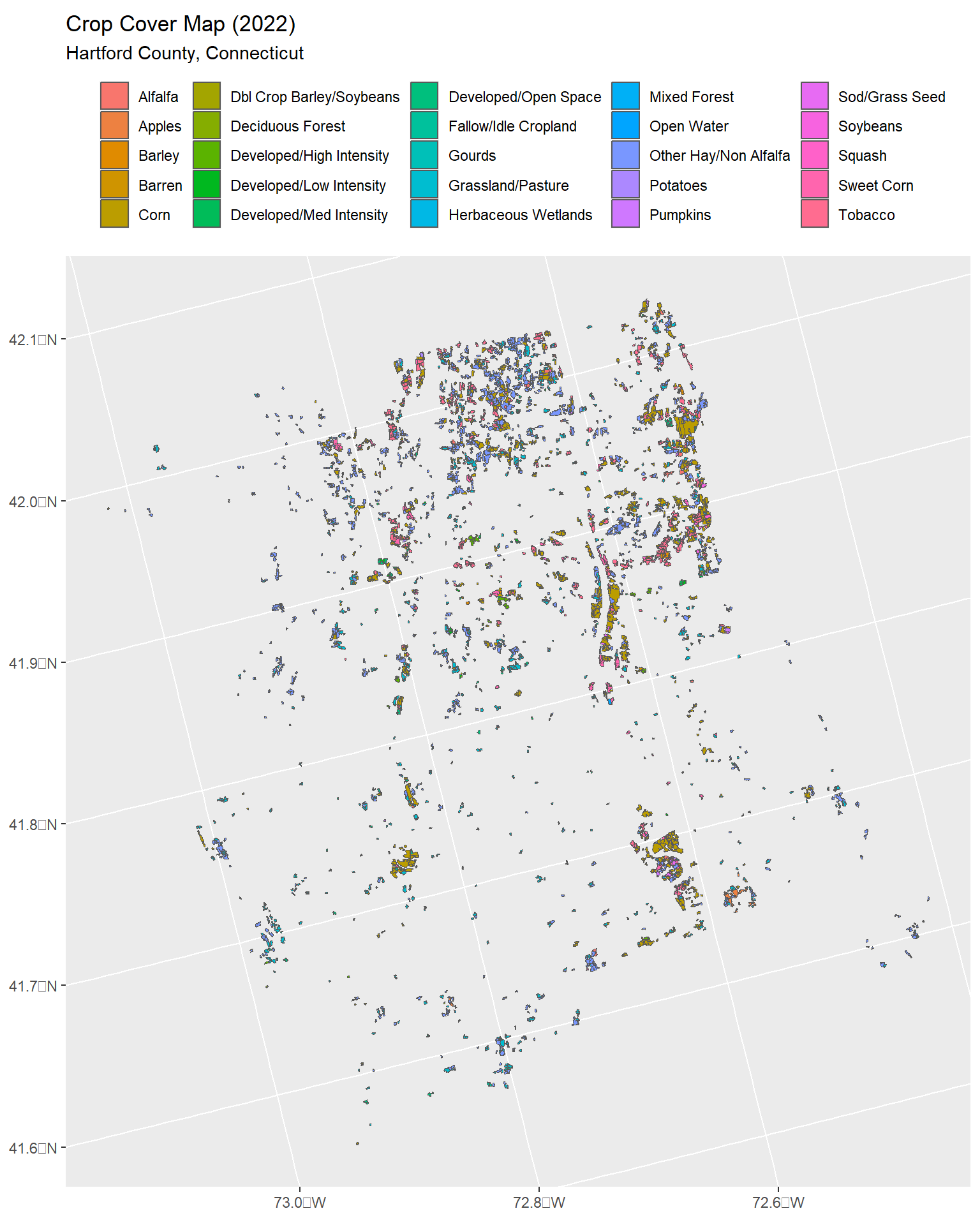

Rows: 3,442

Columns: 23

$ CSBID <chr> "091522009778739", "091522009778745", "091522009778753", …

$ CSBYEARS <chr> "1522", "1522", "1522", "1522", "1522", "1522", "1522", "…

$ CSBACRES <dbl> 2.561646, 4.998030, 4.605023, 3.764729, 2.659328, 12.1047…

$ R15 <int> 222, 176, 37, 37, 61, 222, 36, 61, 1, 36, 61, 36, 222, 22…

$ R16 <int> 61, 37, 37, 37, 37, 61, 36, 61, 61, 36, 12, 36, 12, 61, 3…

$ R17 <int> 11, 37, 37, 37, 37, 1, 37, 1, 1, 36, 27, 37, 1, 11, 36, 3…

$ R18 <int> 11, 37, 37, 37, 37, 1, 37, 1, 37, 37, 1, 37, 1, 1, 36, 37…

$ R19 <int> 11, 37, 37, 37, 176, 11, 1, 11, 37, 37, 61, 37, 12, 11, 3…

$ R20 <int> 11, 37, 37, 37, 1, 11, 1, 11, 37, 37, 11, 37, 11, 11, 37,…

$ R21 <int> 11, 176, 37, 37, 1, 11, 176, 11, 1, 37, 11, 37, 12, 11, 3…

$ R22 <int> 11, 176, 37, 37, 1, 11, 176, 11, 1, 37, 11, 176, 43, 11, …

$ STATEASD <chr> "0910", "0910", "0910", "0910", "0910", "0910", "0910", "…

$ ASD <chr> "10", "10", "10", "10", "10", "10", "10", "10", "10", "10…

$ CNTY <chr> "Hartford", "Hartford", "Hartford", "Hartford", "Hartford…

$ CNTYFIPS <chr> "003", "003", "003", "003", "003", "003", "003", "003", "…

$ INSIDE_X <dbl> 1895864, 1882887, 1884842, 1895255, 1896851, 1897364, 189…

$ INSIDE_Y <dbl> 2348512, 2345240, 2345735, 2348269, 2348659, 2348843, 234…

$ Shape_Leng <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, N…

$ Shape_Length <dbl> 517.9627, 797.8349, 628.0148, 781.6467, 477.5219, 1433.17…

$ Shape_Area <dbl> 10366.61, 20226.31, 18635.87, 15235.32, 10761.92, 48986.1…

$ year <int> 2022, 2022, 2022, 2022, 2022, 2022, 2022, 2022, 2022, 202…

$ STATEFIPS <int> 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, …

$ geometry <MULTIPOLYGON [m]> MULTIPOLYGON (((1895891 234..., MULTIPOLYGON…